Natural Sake with Masaru Terada

During brewing season, sake brewers in Japan are notoriously exclusive to whom they open their doors. Unlike the winemakers and distillers, sake brewers tend to focus exclusively on production during the brewing season, and politely reject or even outright ignore requests to visit. A few weeks before coming to Japan, I sent off a flurry of emails to sake producers as a Hail Mary. What harm could it do?

As the time until the trip ticked down and we still had no responses, I resigned myself to the likely fate that I would have to save my trip to a sake brewery for another time - one outside the brewing season. I pushed those hopes aside and instead shifted my focus to the amazing world of Japan that was unfolding before me.

At the halfway point of our trip, my husband Tyler and I were in the geisha district of Gion in Kyoto. The low-set wooden buildings flanked the stone roads while geisha flitted in and out of their appointments. The lanterns flanking the old street cast golden light on the calligraphy emblazoned on the wooden storefronts. Mesmerized, I barely registered the quick vibration from my phone in my pocket, but still instinctively pulled it out.

“One new email: Masaru Terada.”

My heart stopped. One of the sake brewers had actually responded to me. And this wasn’t just any sake brewer, but Masaru Terada himself - the brewer that I wanted to visit more than any! I held my breath and opened the message.

Masaru Terada invited us to come visit him at his brewery in Chiba! We had the almost unheard-of privilege of visiting this special place. As an added bonus, Masaru informed me that winemaker Alex Prüfer from Le Temps des Cerises from France would be visiting the brewery on the very same day. A natural sake brewer and natural winemaker in the same place? It seemed too good to be true!

I first learned about Masaru and his intricate sake at the RAW natural wine fair in London. Even amongst the hundreds of natural wines, the quality and complexity of his brews managed to spark my initial interest in sake. I was never interested in sake before, as with few exceptions, the sake available in America and Europe are of inferior quality. Inappropriate storage and transportation methods are partially to blame, as sake loses its flavor and character much more quickly than wine.

We woke up that morning, packed our bags, and headed toward the first train. Unfortunately, we went to the wrong platform, and after a hurried sprint with way too many bags, we got to the platform and turned the corner just in time to watch the train doors close. “Maybe this time it’s just not meant to be,” I sighed to Tyler. We stood on the train platform somewhere on the outskirts of Tokyo watching the trains speed by for a minute or two. Tyler decided to call Masaru. The brewer seemed quite surprised that A) I was bringing Tyler with me, B) that we were going to be an hour late, and C) that we had a huge amount of luggage with us.

Luckily Tyler got us back on schedule, and we ended up transferring trains five times to get to the little village of Kozaki located in the rural areas of Chiba. The further into the countryside we ventured, the more beautiful rural scenery started to unfold before us and the more relaxed we became. Carefully tended rice fields, pastures, and small rural villages comprised of old wooden houses and shrines plodded by at the train’s leisurely pace.

We disembarked from the train with our luggage, and a few minutes later Masaru Terada pulled up in a very full blue van. Winemaker Alex Prüfer and his wonderful wife sat in the back with their wine importer Jun Fujiki, while master gardener and Pomme de Terre business owner Hiromi Fujiki was in the front. Masaru drove the entire group to his beautifully tended fields, where the paddies were surrounded on all sides by yellow flowers and wild herbs.

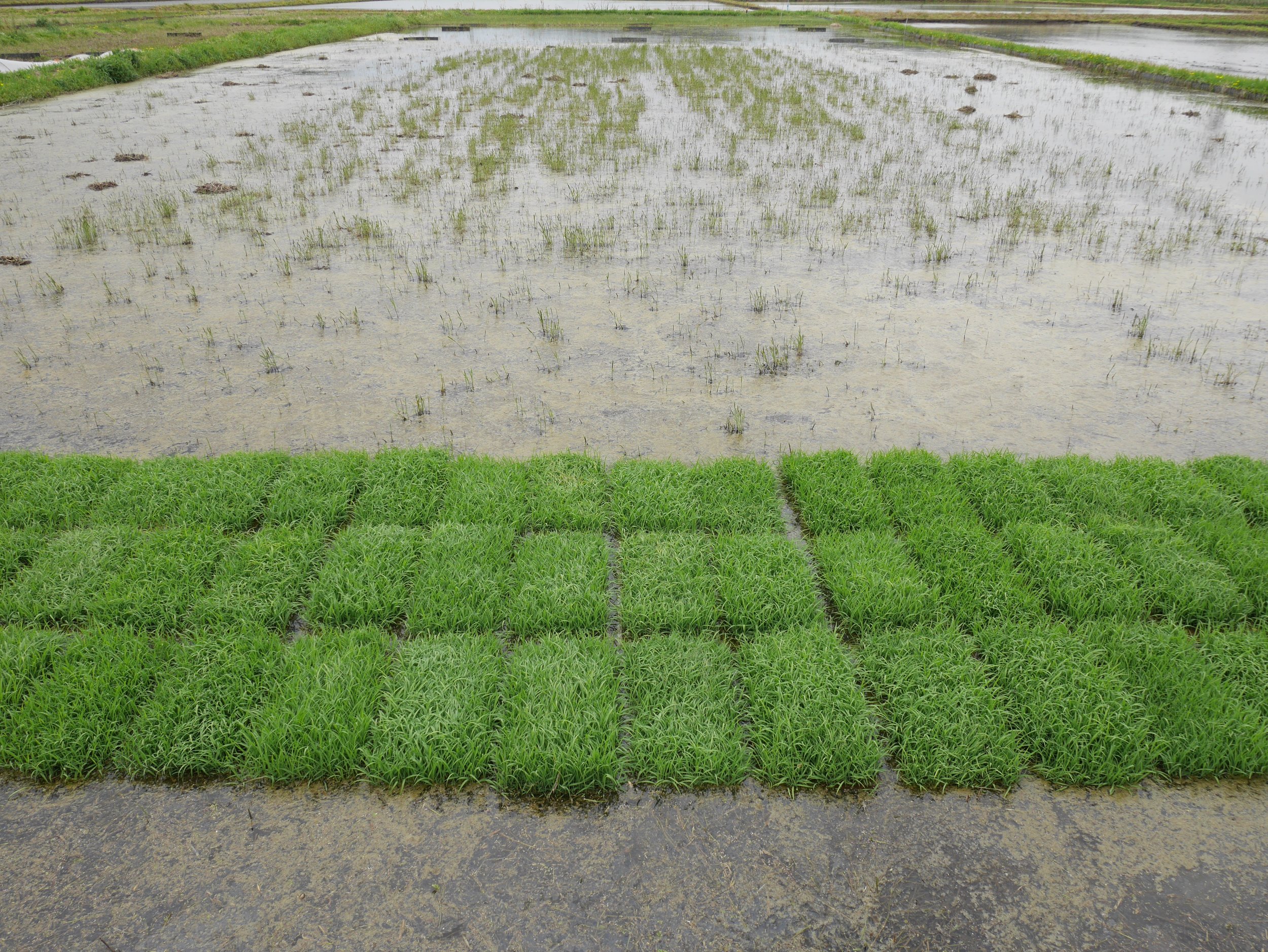

“Rice is the most important part of sake production,” Masaru told us, grinning at his field. His organic approach to farming results in fields that are full of life. Frogs croaked, while grasshoppers jumped out of our way with each step. He showed us his nursery, which was tucked away in the corner. When growing rice paddy, it is important to grow the plants to a certain size where they are viable, and then individually transplant them into the field.

“These sprouts are of the Shindiki rice variety,” Masaru told us. “I started this nursery three weeks ago, and they will be ready for planting in another week.” He continued, “transplanting is a lot of work, but it keeps the plants more organized and allows for easier manual harvest.” Masaru grows five different rice fields on his 1.5-hectare farm, all of which are meticulously leveled and plowed. He takes care to only select the strongest paddy to plant by utilizing a method called saltwater seed selection, where good seeds and bad seeds are separated by the specific gravity of saltwater. In addition to his own paddy, Masaru sources rice from ten other local organic farmers for his brews.

After a trip to rice fields we drove to Masaru’s brewery, “Terada Honke.” From the moment we arrived we felt very welcomed. The brewery and its grounds are from a different time; the old wooden structures were built in a half circle around a is quaint little courtyard. White, fuzzy-looking chickens waddled by a small shrine, while towering overhead is the tall chimney that at one point heated the rice and now serves as the brewery’s symbol.

Terada Honke brewery is more than 300 years old, with its origins dating back to the Edo period (1603-1867) when sake production became prevalent in Kozaki. Because of the fertility of the soil, the quality of the ground water, and the ease of transportation on the Tone River, Kozaki became one of the main suppliers of sake, soy sauce, and miso for the fertile soil, quality ground water and transportation via Tone river Kozaki became one of the main suppliers of sake, soy sauce and miso for what would later become Tokyo.

Although most brewers in Kozaki have turned to commercial brewing techniques, Terada Honke has remained faithful to its traditional approaches. The art of brewing is a family tradition that has been passed down from generation to generation, with Masaru Terada being the 24th successor. Before coming to Terada Honke brewery, Masaru worked as a rice grower and kurabito (brewery worker) in another brewery, but after he married into the Terada Honke family, he took over production from his father-in-law. After the second world war, Terada Honke was modernized along with the rest of the surrounding breweries and adopted commercial brewing methods. It wasn’t until the 1980s that Masaru Terada’s father-in-law re-established the brewery’s natural approach to sake brewing. Masaru has continued making sake this way too much success, even exporting to Europe and supplying some of their most prestigious restaurants.

Just after we jumped out of the car, a dog cheerfully greeted us together with bunch of white chickens. Masaru wanted to take us directly to his brewery facility, but all of the guests were smitten with the funny-looking fuzzy chickens. Their feathers were unusually long, and looked fuzzy and white. After a few minutes Masaru managed to regain the attention of the group, and we followed him into the brewery.

The production facility is built almost entirely out of wood, as are the tools used for brewing. We entered the building and the gentle, pleasant smell of fermenting sake greeted us. Right after the entrance a long set of tables held brown burlap sacks of leftover fermented and pressed rice. Masaru took some out of the bag and we all had a chance to taste some of the sweet yet sour rice lees.

Polishing and steaming

Masaru guided us to the ohitsu, a wooden steamer that looked like a large bowl. He explained that when rice is harvested and brought to the brewery, it first undergoes polishing and cleansing before being steamed. In conventional breweries, 70 percent of the rice kernel is ground away (or “polished”) during sake production, but at Terada Honke Brewery they only polish away between 10 and 30 percent. According to Masaru, this creates a depth of flavors unattainable with highly polished rice.

Masaru’s belief in traditional pre-technology methods of brewing lead him to use only modestly polished rice with a high seimaibuai. Seimaibuai – one of the most important words to know when ordering sake – is the amount of rice remaining on each kernel after polishing. Traditional sake made before the second world war had a seimaibuai of 70 percent. This style of sake is known as junmai – the “purest line.”

After polishing the rice, it is washed to remove all remaining dust and rice bran. This must be done carefully, for polished grains readily absorb water. If too much water is used for too long, the rice can end up sticky and unusable. After the washing and soaking, the rice is dried for one day so that the structure of the rice remains firm. The dried grain is then put into large steamers (koshiki) where it is exposed to steam for 1-2 hours. The rice is then spread out on flat platforms and naturally cooled. Masaru separates the grains into three portions - one for making koji, another to be used as shubo – a yeast starter – and the third for raw material for the brewing and fermentation process.

Koji room

The heart of the Terada Honke brewery, both literally and poetically, is the koji room. Here is where the koji – the mold starter for the fermentation process – develops. Masaru guided us walked through a short wooden door into a small hardwood room and instructed us to remove our shoes. He handed us each a pair of “koji shoes” that are only for use inside the koji room. He opened the room and hurried us inside. The all-wood room looked much like a sauna, with two long wooden tables in the middle. On these tables Masaru lays out the cooled rice and sprinkles the koji spores (aspergillus oryzae) that he has harvested in his rice fields. Masaru hand-mixes the koji bacteria together with the rice, in a process known as inoculation. Over the next 24 hours the bacteria penetrates the rice, incubating it. This process produces an enzyme that breaks down the starch in rice and produces sugar. Alcohol requires glucose – since rice does not naturally contain glucose, brewers must break the starches down into glucose so they can be turned into alcohol and carbon dioxide through fermentation. It takes two nights to prepare the koji, into which which he has mixed this year’s and last year’s mold. Most farmers consider the wild koji that Masaru uses a disease.

During the process of inoculation and incubation the rice becomes green, and then eventually turns black. The process starts at 32 degrees Celsius and naturally increases to 44-45 degrees, at which point they must cool it by hand. The temperature at this process is critical. At the required high temperatures, the enzyme that breaks down starch into glucose is produced, while at low temperatures, the enzyme that breaks down the protein is produced instead. Sake production only happens at higher temperatures.

Mother of sake (shubo) – where the magic happens!

After the rice has been inoculated and incubated with koji, Masaru mixes it with water and steamed rice make the yeast mash that kick-starts the fermentation process. Terada Honke brewery utilizes the traditional way of making mash – the kimoto method – by using living, air-borne lactic acid bacteria to help grow wild yeasts rather than adding commercial lactic acids and yeasts. According to Masaru, this process takes much longer, but is well worth it as a more complex flavor profile develops. Masaru explained to us that the lactic acid bacteria found in the air produces organic acids that reduce pH of the mash. This favors and protects the growth of yeast that is later needed to start the fermentation process. To facilitate the entry of lactic acid bacteria into the mash, Masaru uses a special wooden tool called a kai to stir the mash for 20 minutes every few hours for several weeks (similar to pigage technique in winemaking). This mash-making process takes much longer than at commercial breweries that add artificial bacteria and yeast.

The shubo process must be conducted in a cold environment around 5 degrees, as this is the optimal temperature for lactic acid bacteria to thrive. Most other types of bacteria and yeast dislike the cold, so unwanted bacteria and harmful yeast strains are unable to spoil the mash. Lactobacteria starts at low temperatures and low pH, while fermentation starts with native yeast in warmer temperatures. That is why is so important that brewing is done during cooler months.

Usually groups of workers stand around each wooden vat mashing the mixture, but since we arrived to the brewery after they finished the brewing process, Masaru gave us a mock demonstration. To our surprise, he began singing while pounding down with his wooden kai into the small vat. Masaru does this to “transmit [his] joy to the sake.” Traditional shikomi (preparation songs) are originate from the Edo period where workers sang them both to lift their spirits and to measure the time of mashing.

Fermentation

After fermentation, the mash is put into large enamel-coated steel vats and wood fermenters. More koji mash and rice are then added to the vessel during fermentation. After a month of slow fermentation, the mash is traditionally pressed through cloth. The juice is then allowed to settle.

Terada Honke produces two types of sake - raw and pasteurized. The raw sake is bottled just after pressing and needs to be properly refrigerated. Pasteurized sake takes over a year of maturation before is bottled and ready to be released.

After the tour was finished, Masaru led us outside onto the courtyard. Just when we thought we would say goodbye, he walked over to a large wooden door with on a nearby old building, and, with great effort slid it open. Inside was a tatami-mat room with a low Japanese-style table lavishly covered with numerous bottles of Masaru’s freshly brewed sake sitting in the middle. The vegan lunch was the highlight of the visit – we shared and passed bowls and plates topped with delicious Japanese dishes, some of them quite unique. We savored juicy carrot salads with sake lees, lotus roots and wild mushrooms sautéed with amazake (sweet and sour sake “most”), onigiri with seaweed, homemade bread, and my all-time favorite: shiitake and oyster mushroom pâté served with fresh young garlic, carrots, and daikon radish. Each dish paired perfectly with the raw and pasteurized sakes Masaru served us that afternoon. Masaru’s wife is vegan so all the food brought to us was prepared that way. However, we didn’t miss meat or fish. The textures and flavors of the food and sake blended into the atmosphere of the building and the excellent company to create a wholly unique and unforgettable experience.